(Receive our blog posts in your email by clicking here. If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

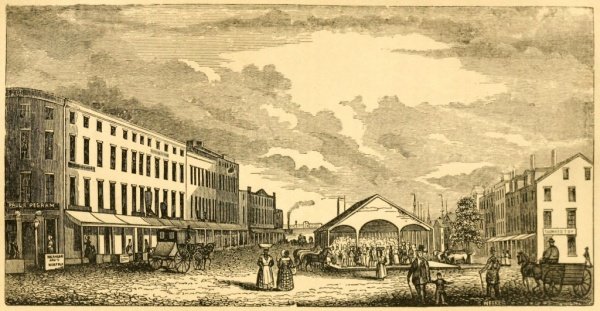

Omar ibn Said was born in 1770 in the West African kingdom of Futa Toro (modern-day Senegal). At the age of 27, he was sold into slavery, and ultimately arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, just before the United States banned the importation of slaves. After an attempted escape from his first master, he was eventually purchased by James Owen, who would go on to serve as North Carolina legislator and as President of the Wilmington & Raleigh Railroad. His brother John also served as Governor.

Owen helped Said learn English by obtaining for him a translation of the Koran. He then acquired for Said (with the assistance of John Louis Taylor, Chief Justice of North Carolina, and Francis Scott Key, composer of “The Star-Spangled Banner”) a Arabic translation of the Bible (which is currently held at the Davidson College Library Rare Book Room). It was on December 3, 1820 that Said was converted to Christianity. He soon joined the First Presbyterian Church of Fayetteville, North Carolina.

His 1831 autobiography, The Life of Oman ibn Said, is the only known native-language autobiography by a slave in America. It was written in Arabic and can be read at Log College Press, along with two English translations. It is a short work, and leaves many gaps in his life story, which Said was not inclined to fill over the course of his ninety-four span - “Omar was noted for being obscure and evasive when speaking about his life in Africa.”

Two accounts by notable Presbyterian ministers give great insight into the story of a man who has fascinated so many. William S. Plumer wrote of him for the New York Observer in 1863:

Meroh, A Native African

In the fall of 1826, I went to Wilmington, N.C., to preach a few Sabbaths in the Presbyterian Church. While there I was visited by a venerable man, a native of Africa. He came to the door of my rooms, entered, and approached me. I rose to receive him. He took my hand between both of his, and earnestly pressed it to his bosom. Our interview was not long, but I received very deep impressions of his moral worth.

I have met him once or twice since, but was commonly hindered from learning much respecting him, as he was much more inclined to hear then to speak — to ask questions than to answer them. Yet from him and from others I have learned the following things.

Meroh was born about the year 1770. If he is still living, as he was by my last advices, he is over ninety years of age. He was born on the banks of the Senegal river, in Eastern Africa. His tribe were the Foolahs. Their religion was Mahomedanism. Many of them had the Koran and read and wrote the Arabic language. I have now in my possession a letter written by Meroh in Arabic, bearing all the marks of expert penmanship.

I write his name Meroh. It was originally Umeroh. Some write it Moro; and some put it in the French form, Moreau. It is commonly pronounced as if spelled Moro.

Meroh’s father in Africa was a man of considerable wealth. He brought up his children delicately. Meroh’s fingers are rather effeminate. They are very well tapered. His whole person and gait bear marks of considerable refinement.

At about five years of age he lost his father, in one of those bloody wars that are almost constantly raging in Africa. Very soon thereafter he was taken by an uncle to the capital of the tribe. Here he learned and afterwards taught the Arabic, especially some prayers used by Mahomedans. He also learned some rules of Arithmetic, and many of the forms of business. When a young man he became a dealer in the merchandise of the country, chiefly consisting of cotton cloths. Some years since I saw in some newspaper an account of this man, which I believe to be quite correct. I make an extract: —

“While engaged in trade, some event occurred, which he is very reluctant to refer to, but which resulted in his being sold into slavery. He was brought down to the coast shipped for Africa, in company with only two who could speak the same language, and was landed at Charleston in 1807, just a year previous to the final abolition of the slave trade. He was soon sold to a citizen of Charleston, who treated him with great kindness, but who, unfortunately for Moreau, died in a short time. He was then sold to one who proved to be a harsh cruel master, exacting from him labor which he had not the strength to perform. From him Moreau found means to escape, and after wandering nearly over the State of South Carolina, was found near Fayetteville, in this State [North Carolina]. Here he was taken up as a runaway, and placed in the jail. Knowing nothing of the language as yet, he could not tell who he was, or where he was from, but finding some coals in the ashes, he filled the walls of his rooms with piteous petitions to be released, all written in the Arabic language. The strange characters, so elegantly and correctly written by a runaway slave, soon attracted attention, and many of the citizens of the town visited the jail to see him.

“Through the agency of Mr. Mumford, then sheriff of Cumberland county, the case of Moreau was brought to the notice of Gen. James Owen, of Bladen county, a gentleman well known throughout this Commonwealth, for his public services, and always known as a man of generous and humane impulses. He took Moreau out of jail, becoming security for his forthcoming, if called for, and carried him with him to his plantation in Bladen county. For a long time his wishes were baffled by the meanness and the cupidity of a man who had bought the runaway at a small price from his former master, until at last he was able to obtain legal possession of him, greatly to the joy of Moreau. Since then, for more than forty years, he was been a trusted and indulged servant.

“At the time of his purchase by General Owen, Moreau was a staunch Mahomedan, and, the first year at least, kept the fast of Rhamadan with great strictness. Through the kindness of some friends, an English translation of the Koran was procured for him, and read to him, often with portions of the Bible. Gradually he seemed to show more interest in the Sacred Scriptures, until he finally gave up his faith in Mahomet, and became a believer in Jesus Christ. He was baptized by Rev. Dr. [William Davis] Snodgrass, of the Presbyterian Church, in Fayetteville, and received into the church. Since that time he has been transferred to the Presbyterian church in Wilmington, of which he has long been a consistent and worthy member. There are few Sabbaths in the year in which he is absent from the house of God.

“Uncle Moreau is an Arabic scholar, reading the language with great facility, and translating it with ease. His pronunciation of the Arabic is remarkably fine. An eminent Virginia scholar said, not long since, that he read it more beautifully than any one he ever heard, save a distinguished savant of the University of Halle. His translations are somewhat imperfect, as he never mastered the English language, but they are often very striking. We remember once hearing him read and translate the twenty-third Psalm, and shall never forget the earnestness and fervor which shone in the old man’s countenance, as he read of the gown down into the dark valley, and using his own broken English, said, ‘Me no fear, Master’s with me there.’ There were signs in his countenance, and in his voice, that he knew not only the words, but felt the blessed power of the truth they contained.

“Moreau has never expressed any wish to return to Africa. Indeed, he has always manifested a great aversion to it when proposed, changing the subject as soon as possible. When Dr. Jonas King, now of Greece, returned to this country from the East, he was introduced in Fayetteville to Moreau. Gen. Own observed an evident reluctance on the part of the old man to converse with Dr. King. After some time he ascertained that the only reason of his reluctance was his fear that one who talked so well in Arabic might have been sent by his own countrymen to reclaim him, and carry him again over the sea. After his fears were removed, he conversed with Dr. King with great readiness and delight.

“He now regards his expatriation as a great Providential favor. ‘His coming to this country,’ as he remarked to the writer, ‘was all for good.’ Mahomedanism has been supplanted in his heart by the better faith in Christ Jesus, and in the midst of a Christian family, where he is kindly watched over, and in the midst of a church which honors him for his consistent piety, he is gradually going down to that dark valley, in which, his own firm hope is, that he will be supported and led by the hand of the Great Master, and from which he will emerge into the brightness of the perfect day.”

This pious man is supplied with a copy of the Arabic New Testament. He says the translation is not good. Yet with the aid of the English he has gained much knowledge of God’s Word. His appearance, at any time I have seen him, was striking and venerable. His moral and Christian character are excellent. No one who knew him well doubted that he was preparing for a better world. Perhaps he has already gone to the rest of the redeemed.

Omar had opportunities to return to Africa as a missionary but declined to do so on account of age and health considerations. He did seek to work with the American Colonization Society to promote the spread of the gospel in Africa in other ways. The Secretary of the ACS, R.R. Gurley, wrote about him thus in 1837:

In the respected family of General Owen, of Wilmington, I became acquainted with a native African, whose history and character are exceedingly interesting, and some sketches of whose life have been already published. I allude to Moro or Omora, a Foulah by birth, educated a Mahometan, and who, long after he came in slavery to this country, retained a devoted attachment to the faith of his fathers and deemed a copy of the Koran in Arabic (which language he reads and writes with facility) his richest treasure. About twenty years ago, while scarcely able to express his thoughts intelligibly on any subject in the English language, he fled from a severe master in South Carolina, and on his arrival at Fayetteville, was seized as a runaway slave, and thrown into jail. His peculiar appearance, inability to converse, and particularly the facility with which he was observed to write a strange language attracted much attention, and induced his present humane and Christian master to take him from prison and finally, at his earnest request, to become his purchaser. His gratitude was boundless, and his joy to be imagined only by him, who has himself been relieved from the iron that enters the soul. Since his residence with General Owen he has worn no bonds but those of gratitude and affection.

“Oh, ‘tis a Godlike privilege to save,

And he who scorns it is himself a slave.”

Being of a feeble constitution, Moro’s duties have been of the lightest kind, and he has been treated rather as a friend than a servant. The garden has been to him a place of recreation rather than a toil, and the concern is not that he should labor more but less. The anxious efforts made to instruct him in the doctrines and precepts of our Divine Religion, have not been in vain. He has thrown aside the bloodstained Koran and now worships at the feet of the Prince of Peace. The Bible, of which he has an Arabic copy, is his guide, his comforter, or as he expresses it, “his Life.” Far advanced in years, and very infirm, he is animated in conversation, and when he speaks of God or the affecting truths of the Scriptures, his swarthy features beam with devotion, and his eye is lit up with the hope of immortality. Some of the happiest hours of his life were spent in the society of the Rev. James King, during his last visit from Greece to the United States. With that gentleman he could converse and read the Scriptures in the Arabic language and feel the triumphs of the same all-conquering faith as he chanted with him the praises of the Christian’s God.

Moro is much interested in the plans and progress of the American Colonization Society. He thinks his age and infirmities forbid his return to his own country. His prayer is that the Foulahs and all other Mahomedans may receive the Gospel. When, more than a year ago, a man by the name of Paul, of the Foulah nation and able like himself to understand Arabic, was preparing to embark at New York for Liberia, Moro corresponded with him, and presented him with one of his two copies of the Bible in that language. Extracts from Moro’s letters are before me. In one of them he says “I hear you wish to go back to Africa; if you do go, hold fast to Jesus Christ’s law, and tell all the Brethren, that they may turn to Jesus before it is too late. The Missionaries who go that way to preach to sinners, pay attention to them, I beg you for Christ’s sake. They call all people, rich and poor, white and black, to come and drink of the waters of life freely, without money and without price. I have been in Africa; it is a dark part. I was a follower of Mahomet, went to church, prayed five times a day and did all Mahomet said I must: but the Lord is so good. He opened my way and brought me to this part of the world where I found the light. Jesus Christ is the light, all that believe in him shall be saved, all that believe not shall be lost. The Lord put religion in my heart about ten years ago. I joined the Presbyterian Church, and since that time I have minded Jesus’ laws. I turned away from Mahomet to follow Christ. I don’t ask for long life, for riches, or for great things in this world, all I ask is a seat at Jesus’ feet in Heaven. The Bible, which is the word of God, says sinners must be born again or they can never see God in peace. They must be changed by the Spirit of God. I loved and served the world a long time, but this did not make me happy. God opened my eyes to see the danger I was in. I was like one who stood by the road side and cried Jesus, thou Son of God, have mercy; he heard me and did have mercy. ‘God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life.’ I am an old sinner, but Jesus is an old Saviour; I am a great sinner, but Jesus is a great Saviour: thank God for it. — If you wish to be happy, lay aside Mahomet’s prayer and use the one which our blessed Saviour taught his disciples — our Father, &c.

In another letter to the same, he writes, “I have every reason to believe that you are a good man, and as such I love as I love myself. I have two Arabic Bibles, procured for me by my good Christian friends, and one of them I will send you the first opportunity; we ought now to wake up, for we have been asleep. God has been good to us in bringing us to this country and placing us in the hands of Christians. Let us now wake up and go to Christ, and he will give us light. God bless the American land! God bless the white people. They send out men every where to hold a crucified Saviour to the dying world. In this they are doing the Lord’s will. My lot is at last a delightful one. From one man to another I went until I fell into the hands of a pious man. He read the Bible for me until my eyes were opened, now I can see; thank God for it. I am dealt with as a child, not as a servant.”

These accounts provide to 21st century readers a look at life as it existed in Africa and in the Southern United States in the early 19th century with all its harshness and yet with the sweet savor of the gospel as it freed the souls of men, if not always their chains. Omar died in 1864 not having received his freedom legally, but the chains which bound his soul had been broken many years hence.

Besides the 19th century original and English manuscript translations of Omar’s remarkable autobiography, there is a 2011 critical English edition, edited by Ala Alryyes, available at our Secondary Sources page.

The life story of a man who was born an African Muslim in the 18th century, who was then sold into slavery and who later became a devoted follower of Jesus Christ in America is a tale that redounds to the glory of God!